Egyptian writing is an awe-inspiring part of this ancient civilization that has left a remarkable legacy. It is a fascinating amalgamation of art, magic, and functionality. While hieroglyphics is the most famous writing system of Ancient Egypt, it was not the only one. The Egyptians also used hieratic and demotic writing. On this page, we will provide you with an introduction to these writing systems, with a particular focus on the beauty and enigma of Egyptian hieroglyphic writing. This will help you appreciate the intricacies of the writing when you visit the many monuments that display it during your trip to Egypt. Take note of everything we explain here to deepen your understanding and admiration for this remarkable feat of human creativity.

The significance of Egyptian writing is unparalleled, not just locally where it was a valuable tool for administration and a magical form of expression for religion, but also globally. It was one of the earliest scripts to be developed, earning Ancient Egypt the distinction of being regarded as one of the cradles of civilization.

The term ‘cradle of civilization’ refers to societies that progressed from prehistory to documented history due, in part, to their use of a written system to record various aspects of their culture and economy, including religion, commercial transactions, legal norms, etc.

Historians identify six of these societies, all of which emerged from the end of the 4th millennium BC to the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC: Mesoamerica (ancient Mexico and Central America), Norte Chico (modern-day Peru), the Indus Valley in the Indian subcontinent, the Chinese in the Yellow River, and most notably, those in the Fertile Crescent: Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. These civilizations developed independently of one another.

Although Mesopotamia is often cited as the civilization that pioneered the use of writing systematically, Ancient Egypt developed its own system of writing with a completely different script: hieroglyphics. The system evolved from simple decorative strokes to a complex set of more or less schematic drawings used to represent sounds and ideas, with more than 6,000 characters estimated to make up this type of Egyptian writing.

Hieroglyphics were used uninterrupted for over 3,500 years, but since the middle of the 3rd millennium, they began to coexist with hieratic writing, a simpler and faster system to execute. By the 7th century BC, hieroglyphics also coexisted with demotic writing, which represented a different language and was even simpler to use for economic and literary purposes. As a result, the use of hieroglyphics was greatly reduced in the last stages of the civilization, and their knowledge was limited to inscriptions on walls in religious temples.

The end of hieroglyphic writing in Ancient Egypt came in the late 4th century AD when the last recordings were made on the walls of the temple of Philae in Upper Egypt. The officialization of Christianity in the Roman Empire led to the closure of the religious temples of Ancient Egypt and the final suppression of that culture.

However, the field of Egyptology brought Egyptian writing, and especially hieroglyphics, back to light. In the first decades of the 19th century, significant progress was made in the study of hieroglyphic writing, and in 1822, the French historian Jean-François Champollion achieved the great breakthrough in that emerging discipline: deciphering the meaning of Egyptian hieroglyphics, primarily thanks to the study of the Rosetta Stone.

Although we often refer to “Egyptian writing” in general, the truth is that hieroglyphics have very different characteristics from hieratic and demotic writing. Therefore, we will briefly review their main features.

One of the factors that made the recent decipherment of hieroglyphics so difficult was the fact that it is based on a mixed system. That is, a certain sign can represent one of these things:

Another factor that makes this Egyptian writing system more complex is the limited representation of vowels. Although there are hieroglyphic signs for them, they are rarely used, which can make words unpronounceable at first glance. However, a common convention is to add ‘a’ or ‘e’ to their reading, although the pronunciation of weak vowels may approach that of strong vowels.

Unlike modern Western languages that are read from left to right or Semitic languages like Arabic or Hebrew that are read from right to left, hieroglyphics can be written and read in various directions. It can be oriented horizontally from left to right or right to left, vertically from top to bottom, and even in boustrophedon style, where one line is written from left to right, and the next line is written from right to left, similar to a snake or ox plowing.

In hieroglyphic writing, some groups of signs appear surrounded by cartouches that contain proper names or titles, particularly those of pharaohs. This technique has two purposes: first, to clearly delineate the name to avoid confusion about its beginning or end, which was significant because an error in reading or pronouncing the name was believed to harm the person referred to. Second, it aimed to protect that person, as the group of signs was enclosed by a knotted rope at one end, creating a symbolic isolation.

Except for personal names, where utmost care was taken to ensure correct reading, hieroglyphics were quite open to interpretation, as mentioned earlier with the absence of vowels. Hieroglyphics did not follow strict spelling rules either, and it was common to omit, repeat or exchange signs. This was sometimes done intentionally to write in an archaic style, such as during the New Kingdom era when they wanted to use some of the turns of phrase characteristic of the Old Kingdom.

Hieroglyphics, the first form of Egyptian writing, were deeply intertwined with the religion of Ancient Egypt. They were often referred to as “divine words” and were believed to have a cosmic origin, as stated by the cosmogony of Memphis. According to this belief, the use of words was the very foundation of the universe, a miracle created by the god Ptah.

Although hieroglyphics were originally developed for practical purposes such as record-keeping, they eventually found their way onto supports that guaranteed the eternity of what was written, such as the stone blocks of temples and palaces, the tombs of the deceased, the jewelry and even funerary objects of the deceased, but also on papyrus when this material was used in the Books of the Dead.

This was because it was believed that by pronouncing the name of a deceased person, they could be brought back to life. Therefore, the proper name had double importance: for practical reasons in earthly life and for the immortalization of the ba (soul) in the afterlife. In this sense, Egyptian writing was a tool that prevented the ba from falling into oblivion and ensured that the person would be remembered for eternity.

Moreover, it was believed that errors in naming the deceased could harm them in the afterlife. This is exemplified by the case of the pharaoh Akhenaten, who during the Amarna Period promoted almost exclusive worship of the sun disk Aton and erected himself as its prophet. After his death, this was considered a genuine heresy, and his name was erased from all temples. According to some theories, this was not only to eliminate him from history but also to sabotage his life in the afterlife, taking advantage of the magical nature of Egyptian writing.

Another reason for the importance of hieroglyphics in Ancient Egypt was their aesthetic value. Whether carved, painted, or inscribed on various surfaces, such as temple walls, funerary enclosures, or stone stelae, the visual impact of hieroglyphics is remarkable. They contributed to the creation of a suitable atmosphere for the worship of the gods, and for this reason, many consider hieroglyphics as the most beautiful writing system ever used by humans.

Visiting the spectacular temples of Ancient Egypt presents a great opportunity to practice your knowledge of Egyptian writing, especially hieroglyphics. While it may seem daunting at first, with patience, a keen eye, and the help of a guide, you can decipher much of the information presented to you.

Learning a language takes time and effort, but you can carry a pocket grammar guide to consult the signs of this ancient writing system when needed. Alan Henderson Gardiner, a British Egyptologist of the 20th century, compiled a comprehensive system of hieroglyphics by grouping them into more than twenty thematic categories, including gods, men, women, and buildings. You can also find other pocket guides based on his work or other experts in the field.

When we talk about “Egyptian writing,” we are not only referring to hieroglyphics, which are more famous and evocative due to their beauty and magical attributions. This concept also includes hieratic and demotic writing, which we will review below to understand their differences.

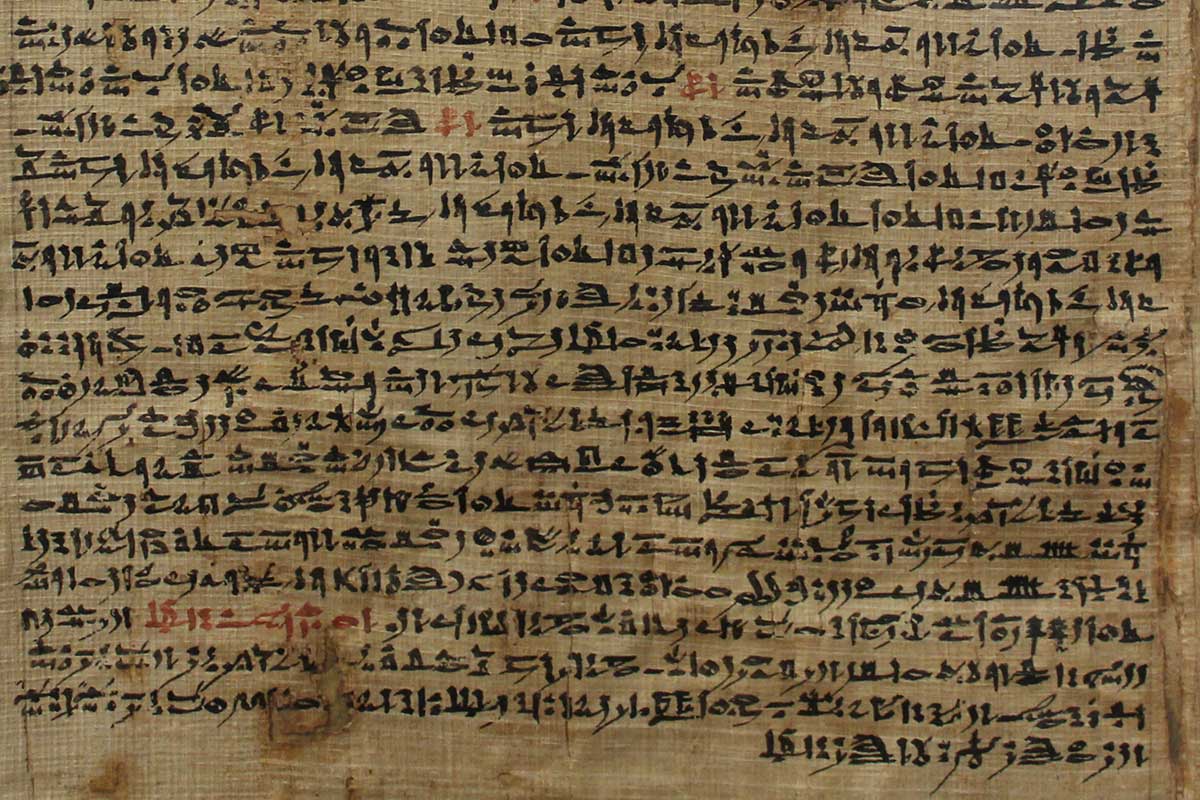

Hieroglyphics were not the most efficient writing system for everyday use, which led to the development of hieratic writing in the mid-third millennium BC. Hieratic was a simplified version of hieroglyphics, adapted for use on papyrus and other materials such as wood, leather, and ostracas. It was primarily used for administrative purposes, such as letters, accounting, and legal texts, but it was also used for religious purposes.

Hieratic signs were more stylized and schematic than hieroglyphics, making them more suitable for writing with a reed pen and black ink, the primary writing tools at that time. Hieratic was also used for sketches on ostracas before transferring the writing to more expensive papyrus.

While hieratic writing was commonly used on papyrus, it was also used on clay tablets through incisions, much like Mesopotamian cuneiform writing. It’s important to note that clay tablets were not exclusive to hieratic writing and that the oldest discovery of this type occurred in Umm el-Qaab (near Abydos), where vessels with Egyptian hieroglyphic writing using this method were found and date back to between 3400 and 3200 BC.

In any case, returning to the topic of hieratic Egyptian writing, it was more widely known and used than hieroglyphics, which were considered truly sacred. Hieratic writing had a much greater presence in daily life, even though it was not taught as widely as hieroglyphics.

Here are some of the main characteristics of hieratic Egyptian writing:

Similar to the evolution of hieratic from hieroglyphics, demotic writing emerged as a more practical and simplified form of hieratic. It was primarily used for everyday purposes such as contracts, economic accounting, and other daily matters. Demotic was also a language in itself, which further simplified the ancient Egyptian language.

The development of demotic writing and its alphabet was a gradual process that began in the mid-7th century BC. However, it did not replace hieratic, which continued to be used until the Roman domination era. Demotic had a limited lifespan as it was gradually displaced by the Hellenistic Greek language for official purposes and important documents from the 2nd century AD.

Unlike hieratic, demotic had a more popular and oral character, which is reflected in its name given by the Greeks: demotika or ‘of the people’. It should not be confused with Greek demotic, which had a similar popular concept but was unrelated to the Egyptian language. Demotic is, however, related to the Coptic language, which it greatly influenced. It was used by the early Christians of Egypt and is still used today as a liturgical language.

The mystique surrounding hieroglyphs was partly due to the fact that only 1% of the population could read and interpret them. This exclusive group included not only the priestly caste who needed to understand them for their religious duties but also the scribes. Scribes had the privilege of possessing divine wisdom, which was believed to be bestowed upon them by the god of Egyptian writing, Thoth. They were responsible for transcribing this knowledge onto various media, especially the Books of the Dead.

However, scribes also used Egyptian writing for practical purposes. For instance, they recorded the floods of the Nile, which was critical for organizing the agricultural production of the country, and carried out inventories in granaries for food supply purposes, among other tasks.

When discussing Egyptian writing, we cannot overlook the Books of the Dead, which were its finest example during the New Kingdom. These funerary texts would be better translated as the “Books of Coming Forth by Day” or “into the Light” as they narrated the awakening of the dead after death to face the Judgment of Osiris.

Written on papyrus rolls and adorned with polychrome vignettes depicting the deceased and the gods involved in the process, these unique documents combined hieroglyphic or hieratic Egyptian writing with art and painting.

Given their spiritual and economic value, it is no surprise that the Book of the Dead was highly prized. It is believed that the cost of these writings could equal an entire year’s salary. Initially reserved for the royal family, they were later commissioned by members of the social elite, including priests, officials, and scribes, with a predominance of male owners.

For the most part, they had no fixed structure, but from the 26th dynasty (Saite period), they adopted a more or less common order. Typically, they began with chapters dedicated to the deceased’s entry into the tomb and descent to the underworld. A thorough explanation of the gods followed, and the deceased was “awakened” to travel in the solar barque during the day, reuniting with Osiris in the underworld at nightfall. In the final chapters, the dead were claimed as candidates for eternal life.

Many of these books, the pinnacle of Egyptian writing, are now on display in museums worldwide. Fortunately, visitors to this country can also see some of them, such as the one belonging to Maiherpri, originally deposited in the tomb of this nobleman in the Valley of the Kings in Thebes, which is available for viewing at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Fill out the form below to receive a free, no-obligation, tailor-made quote from an agency specialized in Egypt.

Travel agency and DMC specializing in private and tailor-made trips to Egypt.

Mandala Tours, S.L, NIF: B51037471

License: C.I.AN-187782-3