Main Characteristics of Ancient Egyptian religion

First of all, it is important to note that, although we use the generic term “Egyptian religion,” it cannot be said that there was a single set of beliefs. It was not homogeneous either among the different regions or throughout all the historical periods that made up the more than 3,000 years of Egyptian civilization. On the contrary, there were significant variations among them, leaving ample room for the veneration of local deities.

This latter point highlights another key characteristic of Egyptian religion: its polytheism. While many current religions are monotheistic, such as the majority and official religion of modern Egypt (Islam) or the minority religion in the country (Coptic Christianity), in ancient Egyptian religion, there was a pantheon made up of numerous deities. Each of them was the protector of different elements of nature or daily life. Some of these gods could have the status of supreme god or even creator god, a rank that varied depending on the historical period or region in question.

This enormous variety of deities among different periods and regions led to another characteristic of Egyptian religion: syncretism. That is, the assimilation of some deities with others, sometimes resulting in new gods that mixed attributes of both.

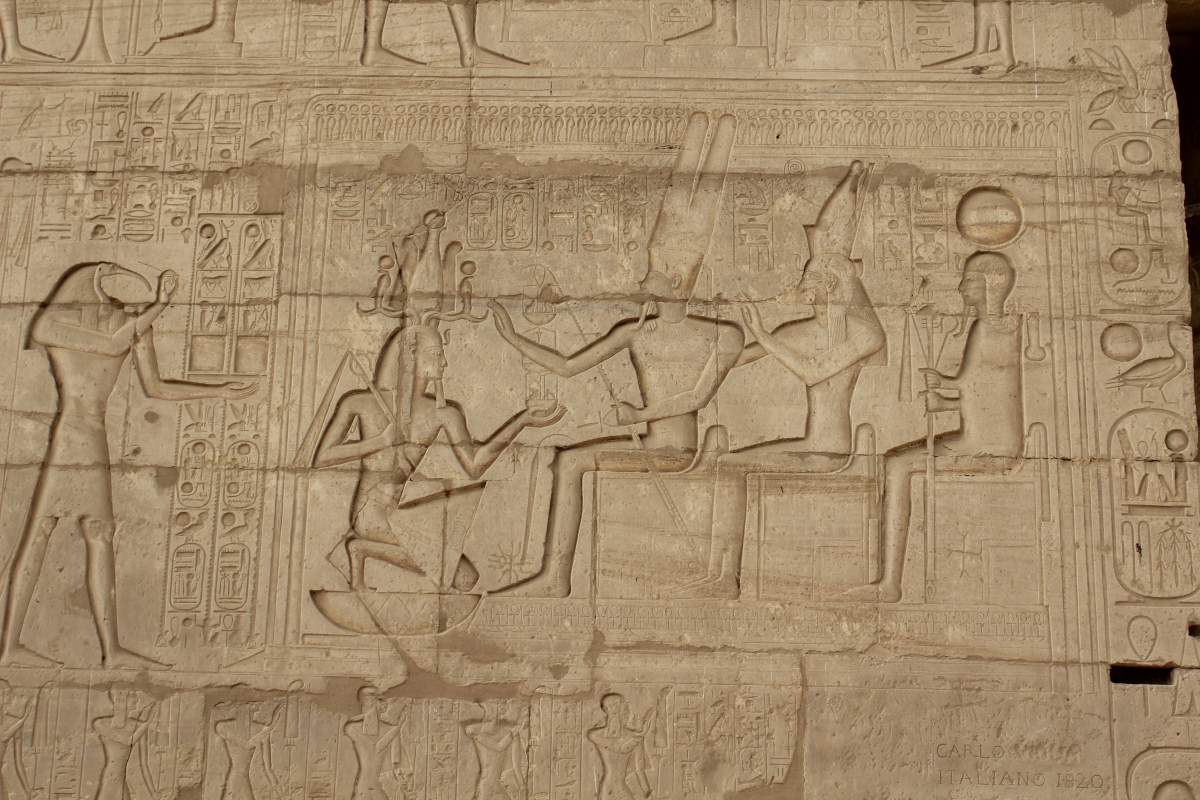

The ways in which believers represented the gods of Egyptian religion are also very striking. They usually did so in the form of an animal, a human form, or a mixture of both, generally with a human body and an animal head or other specific features such as wings and horns. This resulted in creations full of imagination and visual impact that still move those who contemplate them today.

But Egyptian religion was not a mere factory of gods with improbable appearances designed to impress its believers. On the contrary, its set of dogmas was truly complex, and its deities were the perfect vehicle to explain the origin of the universe, to guide the lives of believers, and to promote their eternal life in the afterlife.

Cosmogonies About the Origin of the Universe

As we were saying, one of the great pillars of the Egyptian religion was the explanation of the origin of the universe (cosmogony). In this aspect, there was no homogeneity either, since at least three cosmogonies are identified: those discovered in the sanctuaries of Heliopolis, Hermopolis, and Memphis. However, they had several aspects in common: the belief that life originated from the waters of Chaos (or Primordial Ocean), that the first terrestrial formation was a primordial hill, and that the gods participated in that miracle. These are, in summary, their respective theories:

- Heliopolis: The Sun god Atum emerged from the waters of Chaos, creating himself and the gods Shu and Tefnut (Air and Moisture). They, in turn, created Geb (Earth, male god) and Nut (Sky, female goddess). And from them, Isis, Nephthys, Osiris, and Set were generated. This set of nine primordial gods is called the Ennead (from the ancient Greek ennea, meaning nine).

- Hermopolis: it is based on the primordial existence of eight gods who formed an indissoluble and liquid entity. They were four pairs (Nun-Naunet, Heh-Heket, Kuk-Kauket, and Nia-Niat) and had masculine-feminine concepts. Therefore, their union also expressed the idea of a beginning, which occurred after a great cataclysm triggered by the imbalance in these pairs. In that cataclysm, a kind of primitive Big Bang was generated, which produced the god of wisdom, Thoth, and a mound with a cosmic egg, from which the solar god Ra emerged. This set of eight gods is also called the Ogdoad (from the ancient Greek okto, meaning eight).

- Memphis: it is the simplest of these three cosmogonies of the Egyptian religion, as it attributes the creation of the universe to a single god, Ptah, who transformed the inert waters of Chaos into reality, conceiving it with thought (heart) and materializing it with the word (language). And from this divinity, the rest were originated: Atum, Nun, Nunet, and all the others. For some experts, this Memphite theory of creation was the one that influenced the biblical account of Genesis.

The Triads - Another Concept with Genesis Meaning

Similar to cosmogonies, triads are groups of three gods consisting of a father god, a mother goddess, and a son, emphasizing the idea of birth and genesis of life, which is recurrent in Egyptian religion. By the way, this idea could have influenced the concept of the Holy Trinity in Christianity, according to some authors.

Triads had great significance throughout the history of Egyptian civilization, including the Greco-Roman period, during which mammisi (small temples dedicated to divine birth located near or within larger ones) were constructed. The following are the most important triads in Egyptian religion:

- Osirian triad (Osiris, Isis, and Horus): The main deity is Osiris, the god of resurrection and agricultural fertility. However, his sister Isis and their son Horus were also important. Isis was often considered the mother goddess and protector of the pharaohs, while Horus was often identified with the pharaohs. This triad was perhaps the most widespread and enduring in Egyptian religion.

- Theban triad (Amun-Ra, Mut, and Khonsu): This triad was widely spread after Thebes became the capital, especially during the New Kingdom. The main deity is Amun, merged with Ra. They were paraded during the Opet ritual at the Karnak Temple.

- Memphis triad (Ptah, Sekhmet, and Nefertum): The most important deity is Ptah, the creator god, while Sekhmet is his wife, and Nefertum is their son. This triad was mainly spread during the New Kingdom.

- Elephantine triad (Khnum, Anuket, and Satis): Widely spread in ancient Nubia, in the southern part of the country. The main deity and creator god is Khnum.

- Esna triad (Khnum, Anuket, and Seshat): This triad is very similar to the previous one, but in this case, the daughter is Seshat, the goddess of books.

Gods of Ancient Egyptian religion

If cosmogonies explained, in one way or another, the origin of the universe, the gods that emerged from that origin guided and protected the lives of their believers during earthly existence. They were very present in the day-to-day lives of ancient Egyptians through rituals, offerings, and other acts of veneration. Each one occupied a specific place in maat or divine order, with specific functions for maintaining general harmony and the ability to influence natural events and human lives.

It is important to note that the gods we will see below were not independent, but interacted with each other, giving rise to events and legends to explain their roles and natural phenomena. All of this gave rise to the mythology of Egyptian religion, which was of great richness and has been reconstructed thanks to funerary texts, devotional hymns recited by the faithful, and writings by Greeks and Romans who came into direct contact with Egyptian civilization.

List of the Main Gods

Below we list alphabetically the main divinities of the Egyptian religion. However, the complete list of the pantheon of gods is very extensive, with a number that varies depending on the assimilations that are accepted. For example, only in the Judgment of Osiris can we count more than 40 participating gods, which is a key myth of the Egyptian religion and which we explain at the end of the page.

Often they present different interpretations depending on the region or historical period, or even assimilations as a result of the aforementioned syncretism. Therefore, we also mention the most important variations within each case.

- Amun: was the local deity of the city of Thebes, replacing Montu. His main temple of worship was that of Karnak. He was considered a creator and celestial god, and therefore sometimes adopted that skin coloration. He was usually represented with a human body, with a headdress of two long symmetrical feathers and a short skirt from which an animal tail hangs. He also often holds an ankh and a uas scepter.

- Amun-Ra: after the rise of Thebes to the rank of capital during the Middle Kingdom, he became the king of the gods, especially after his fusion with Ra, the god of the sun, achieving national rank and being the protagonist of what sometimes seemed almost like a monotheism in Egyptian religion, with the rest of the gods as an extension of him. His supreme character caused the Greeks to identify him with Zeus and the Romans with Jupiter.

- Amonet: a goddess of mystery who brought the wind from the north, symbolizing life. She was highly revered in Hermopolis, although also in Thebes. As a deity closely associated with Lower Egypt, she is often depicted as a woman wearing the Red Crown. At other times, she appears with a frog’s head, a snake’s head or even as a complete serpent, holding the uas scepter and the ankh symbol. Her cult became prominent during the New Kingdom period.

- Anubis: the guardian deity of cemeteries and tombs, and also the protector of embalmers. He is depicted with the head of a jackal, which was a scavenging animal that threatened burial sites in search of food.

- Anuket: the wife of Khnum in the triad of Elephantine, she is a goddess of water and carnal pleasures. Highly revered in ancient Nubia, she is also the protector of the first cataract where the Nile ceased to be navigable, hence regulating its water level. She is often portrayed with a woman’s body and a large crown of feathers, holding ankh and papyrus scepters. She is associated with the gazelle.

- Apis: one of the various fertility gods in Egyptian religion, but in this case, not of the land or humans, but of cattle. In fact, he is represented as a sacred bull or a man with a bull’s head, often accompanied by the solar disk. He was the son of Isis, who conceived him through a sunbeam. One of the main places where he was worshipped was the Saqqara necropolis in Memphis.

- Aten: a solar deity represented by the solar disk, from which rays emanated towards the faithful, who received them with open arms. His worship created a genuine schism in ancient Egypt, known as the Amarna period. In this period, King Akhenaten (also known as Amenhotep IV or Amenophis IV) promoted him as the creator and supreme god, and himself as the envoy and prophet on earth. He was mainly venerated in the city of Akhetaten, built by the pharaoh and located in the present-day region of Amarna.

- Atum: present in the cosmogonies of Heliopolis (as a creator god) and Memphis (as a god emerged from the heart of Ptah), he was one of the solar gods of the Egyptian religion. He was usually represented with a human body, a double crown, and a beard. Sometimes he presented a lobster or ram’s head, and on other occasions as a phoenix bird.

- Atum-Ra: due to similarities in meaning and iconography, these two deities were sometimes merged. In other cases, Atum was only the manifestation of the sunset of the solar god Ra.

- Bes: one of the most grotesque-looking divinities in the Egyptian religion, with a dwarf and animalistic appearance. He was widespread during the New Kingdom. He was the protector of women and children, especially during childbirth. And he is associated with love and sexual pleasure.

- Geb: one of the creator gods, according to the Heliopolitan cosmogony. He was the son of Shu and Tefnut and represented the Earth, although he later passed on his authority over it to one of his sons, Osiris. Among his most specific functions was to guard the gates of Heaven (Duat), watch over the weighing of the deceased’s heart during the Judgment of Osiris, and hold the unjust spirits of the deceased as prisoners. He was sometimes depicted with a green body, and more commonly as a man with a goose on his head, sometimes lying on the ground referring to himself as the personification of the Earth.

- Hathor: goddess protector of love, beauty, and pleasure. Her main cult city was Dendera. Paired as a consort or as a mother of Horus and Ra. And since these were closely linked to royalty, the pharaohs considered her their symbolic mother on Earth. The two most common ways of representing her are as a cow (due to her maternal meaning) and as a woman with a cow-horn headdress, with a sun on her head and her characteristic bead or menat necklace.

- Heket: one of the different divinities related to fertility. In this case, she was a goddess who protected childbirth, helping as a midwife. Placing the ankh on the newborn’s nose, she provoked his breathing. Her assistance in childbirth extended beyond men, as she also facilitated the birth of the sun every morning. Already mentioned in the pyramids from the earliest dynasties, in the Old Kingdom and worshipped in Hermopolis Magna, as she is part of its cosmogony as a goddess participating in the creation of the world. But her greatest presence is in the mammisi. The animal most associated with her is the frog, being represented in full as this amphibian or as a woman with its head.

- Horus (Hor among the Egyptians): the son of the goddess Isis and the god Osiris (after his resurrection), he was usually represented as a falcon or as a man with a falcon’s head. All kings identified with him during their earthly lives, although after death they did so with Osiris. He was already known in the predynastic period, so he is at the origins of the Egyptian religion.

- Ra-Horakhty: association between the sun god Ra and Horus during the New Kingdom.

- Imhotep: Imhotep is an atypical god in the Egyptian pantheon, as his elevation to the rank of god occurred very late, during the Ptolemaic era. In fact, he was an Egyptian scholar who lived during the Old Kingdom era and, due to his wisdom, was venerated in temples. He was a doctor, astronomer, and, above all, an engineer and architect, probably the first in the history of humanity. His most famous work is the stepped pyramid of Saqqara. Once deified, he was considered the god of medicine and wisdom, the patron of scribes, and identified with Nefertum and Thoth. He was usually depicted sitting, as a scribe, with a papyrus on his lap.

- Isis: Isis is a goddess of magic and one of the most important deities in the Egyptian religion. She was part of the group of gods who starred in the cosmogony of Heliopolis. She is usually represented as a woman on whose head a throne rests, holding a papyrus staff in one hand and an ankh in the other. Since the New Kingdom, she began to be associated with Hathor, often adopting her attributes (headdress with sun and cow horns). She is famous for the myth of Osiris, according to which she reassembled the murdered and dismembered body of that god, thus forming the first mummy, to later conceive Horus. Since the pharaohs identified with Horus, they considered Isis their divine mother. She was attributed the ability to influence fate and protect the kingdom. Her main cult center was on the island of Philae, one of the last bastions of Egyptian religion. In fact, her cult multiplied in the final stages of this civilization, as no important temples were built in her honor until the XXX dynasty (4th century BC).

- Khnum: Khnum is a creator god according to the Elephantine triad, and his veneration was centered in ancient Nubia. He is usually represented with a ram’s head, often carrying the ankh, the scepter uas, and the Atef crown. Khnum is closely related to the Nile, as with its mud he modeled human beings, giving them shape on his lathe. Tired of this work, he placed a part of said lathe in the belly of each woman, thus explaining the miracle of life and also placing him as a god of fertility.

- Khonsu: Together with Amun-Ra and Mut, Khonsu was part of the Theban triad. He was a lunar god and therefore usually depicted with a disk of this satellite over his head. Protector of doctors and patients, he had healing powers and repelled evil spirits. He was also associated with the fertility of the earth, which is why he often showed green skin. His body was usually in the form of a mummy and could carry numerous symbolic elements: scepter uas, Dyed pillar, staff, heqa or nejej. Other versions show him as a man with a falcon’s head.

- Maat: Maat was the concept used in Egyptian religion to refer to cosmic and universal harmony, as well as truth and justice. Sometimes she adopted the representation of a standing or seated goddess, wearing ostrich feathers, which were the element used to weigh the hearts of the deceased in the Judgment of Osiris and thus calibrate their sins. She could also carry an ankh and a scepter uas.

- Min: god of the moon, vegetation, fertility, and protector of miners and merchants. He is often depicted with black or green skin and an erect phallus. He wears a crown of feathers and holds a flail (nejej) over his head. His worship was widespread, both geographically and temporally, from the predynastic period to the Roman era.

- Montu: one of the oldest deities in Egyptian religion, initially worshipped as a solar god and later as a god of war, to whom pharaohs would entrust their protection. He is represented as a man with the head of a hawk, sometimes with the head of a bull. He is often crowned with feathers, a sun disk, and an ureus. The main city where he was worshipped was Hermontis, but he also appeared in other cities such as Thebes, Tod, and Nubia.

- Montu-Ra: Montu was assimilated with the god Ra, specifically representing the destructive power of solar rays.

- Mut: the wife of Amun according to the religious beliefs spread in Thebes from the New Kingdom period, displacing Amonet in this role. Considered a mother goddess and of the sky, the Greeks assimilated her to Hera. As a mother goddess, she is often depicted as a woman with a Double Crown or Sejemty. And as a goddess of the sky, she could show attributes of a vulture.

- Nefertum: a god closely associated with the theology of Memphis, considered the son of Ptah and Sekhmet, forming a triad. He symbolized the birth of the sun and was, in fact, the representation of the child Atum. He is usually depicted as a man with a lotus flower on his head, a flower that according to Memphite mythology emerged from the primordial waters of Nun and contained this deity within it. Other attributes he carried were the ankh, the uas scepter, and two high feathers on his head, which were occasionally those of a lion. Among his functions was to watch over the eastern border, where the sun rose. He was also worshipped in other cities such as Buto or Hermopolis Magna.

- Neith: a goddess of funerary rites and protector of war and hunting, widely venerated in Lower Egypt. She is one of the oldest deities in Egyptian religion, dating back to the predynastic period, but in the New Kingdom, she evolved into a concept of a divine mother, creator of gods and men. She is sometimes depicted wearing the Red Crown, a bow and arrows, or the uas scepter and ankh. She was also depicted, either in full or just her head, as a cow, fish, lioness, bee, or scarab. Some places closely associated with her worship were Sais, Tanis, or El Fayum.

- Neftis: the sister of Osiris and, therefore, one of the protagonists of the Ennead of the cosmogony of Heliopolis. She appears alongside Osiris as the protector of mummies and is often depicted as a woman with a hieroglyph expressing her name over her head.

- Neit (or Neith): A funerary goddess and protector of war and hunting, Neit is highly revered in Lower Egypt and is one of the oldest deities in Egyptian religion. Her appearance dates back to the predynastic period, and during the New Kingdom she evolved into a concept of a “divine mother” who creates gods and humans. Neit is sometimes depicted wearing the Red Crown, a bow and arrows, or the uas scepter and ankh. She is also represented in various forms, including a cow, fish, lioness, bee, or scarab. Sais, Tanis, and El Fayum are some of the places closely related to her cult.

- Nut: One of the creator goddesses according to the cosmogony of Heliopolis, Nut symbolizes the sky and is usually depicted with her elongated and arched body enveloping the scene, serving as the celestial vault. Her limbs are the pillars on which the sky rests.

- Osiris: The god of fertility and agriculture, Osiris is associated with the Nile floods and is one of the most important gods in Egyptian religion, particularly in Upper Egypt. He was one of the first to be worshiped and one of the last (his cult remained in the temple of Philae until the 6th century AD). Osiris is also part of the Heliopolitan cosmogony and is often depicted with a throne, like his sister Isis, as he was also a mythical king. He was murdered and dismembered by his brother Seth, but Isis magically reassembled him, creating the first mummy, and later conceiving Horus. Therefore, he is considered the savior of death and lord of the underworld. Abydos was his center of worship and a pilgrimage site for believers who sought to achieve eternity. Osiris is usually depicted mummified with green skin to express his relationship with vegetation, and he wears the crown of Upper Egypt on his head.

- Ptah: The creator god according to the cosmogony of Memphis, Ptah was the patron of artisans and workers and was considered the “master builder” of the world. His main city of worship was located in Memphis. Ptah is often depicted with a straight beard (unlike the curved beards of the other gods), a shaved head, the Djed pillar as a symbol of stability, and the uas scepter and ankh.

- Ra: One of the most important gods of the ancient Egyptians, Ra was the god of the sun and the creator of life. He was responsible for ensuring that the cycle of life and death was fulfilled, which was symbolized by his daily and nightly travels. Ra was often represented as a man with a falcon head and a solar disk above it. His main city of worship was Heliopolis, which the Greeks called Iunu, but changed the name to express the meaning of “city of the sun” in his honor. Depending on the time of day, he was often represented in three different forms:

- Khepri (or Jepri): Represented the dawn. He took the form of a beetle or a man with a beetle head. Temples were not erected in his honor, but large stone sculptures were made within other complexes, such as in the temple of Karnak.

- Horajti: The manifestation of the sun at its zenith. As this was its culmination, it was represented with its most characteristic attributes, such as the falcon head (sometimes that of a ram or feline) and the solar disk. It showed red-colored skin, standing or sitting.

- Atum: Manifestation of dusk, associated with shadows, although in Egyptian religion, he was often also conceived as a sun god in his own right.

- Ra-Horajti: see Horus

- Montu-Ra: see Montu

- Amón-Ra: see Amón

- Atum-Ra: see Atum

- Satis (or Satet): Daughter of Khnum and Anuket in the Elephantine triad, so her worship was also widespread in ancient Nubia. She is the goddess of Nile floods and therefore related to fertility. Satis is often depicted wearing the Hedyet White Crown, carrying an ankh, and with bows and arrows. She is associated with gazelles or antelopes and often exhibits their features.

- Sekhmet: A goddess whose name meant “the powerful” or “the terrible.” She symbolized various ideas such as war, revenge, or healing. Her main place of worship was Memphis. Her mythical and fearsome force was directed against the enemies of the kingdom. She usually appeared as a woman with a lion head (but with a mane) and could display different attributes of power, such as the ureus or the solar disk. She often wore red clothing as a reference to the blood of battle.

- Seshat: The goddess of books, part of the Esna triad, where she was revered, as well as in Hermopolis Magna. Here, she also assumes the protective function of architects and another broader measuring function: time to create the calendar or the land to build on. Her iconography is peculiar, as she is often represented as a woman with a leopard skin dress and a star headdress, as she was in charge of observing them to make different temporal calculations. She also usually holds a scribe’s palette and a reed pen. Sometimes she was identified with Isis.

- Seth (or Set): god of the underworld (Duat) who represents negative or very feared ideas by believers, such as riots, desert storms, or drought. However, it is not appropriate to attribute all of this to evil, but rather to his impulsive character and brute force. In fact, he is one of the gods who participated in the origins of the Universe, according to Heliopolitan cosmogony, and is the brother of Osiris. He was responsible for the death of Osiris, driven by feelings of envy: his father Geb distributed Egyptian land unevenly, giving fertile land to Osiris and the desert to Seth, where he ended up in exile. In any case, he had important functions within Egyptian mythology, such as guarding the solar god Ra’s boat and protecting the pharaohs of some dynasties (II, XV, and XIX) in matters of war. For all this, he is equally respected and feared in Egyptian religion. He can be recognized with an animalistic appearance, close to monstrosity, with attributes of animals such as pigs, crocodiles, donkeys, hippos, fish, or snakes, in a peculiar mix that denotes the strange character that the Egyptians attributed to him from the earliest moments of this civilization.

- Shu: god protagonist of Heliopolitan cosmogony for being the son of the creator god Atum. He represented Air or Atmosphere and his great mission was to keep Heaven (goddess Nut) and Earth (god Geb) separated to avoid absolute chaos. He is often associated with the vital energy that moves the universe and living beings. He was greatly venerated during the Ramesside period (New Kingdom). He is usually represented as a man with an ostrich feather headdress, holding the ankh and the uas scepter. In addition to Heliopolis, his cult was widespread in Memphis, Dendera, and Edfu.

- Sokar: funerary deity who guarded the entrance to the underworld or Duat. God of darkness and protector of the dead in Egyptian religion. He was already revered since the first dynasty and is present in the necropolis of Saqqara (Memphis), among others. For all this, iconography often shows him as a mummy with a hawk head and a feather headdress. He can also carry the uas scepter, the ankh, or an Atef crown, sometimes sitting on a throne.

- Taueret (or Tueris): goddess of fertility, protector of pregnant women. Her appearance was very striking: a pregnant creature with dark skin and a hippopotamus head, dragon tail, voluminous breasts, and feline legs. She sometimes wore horns and a solar disk. Her cult can be seen in temples such as Karnak in Thebes and in Heliopolis, as well as in other places in Upper Egypt, such as Abu Simbel.

- Tefnut: sister of Shu and, therefore, sister of the Heliopolitan creator god Atum. She is the goddess of moisture and symbolizes phenomena such as dew and other natural processes. Some of the places where she was venerated were Dendera and Leontopolis. As for her iconography, she usually appeared as a woman with a lion’s head and mane, ankh, ureus, and uas scepter.

- Tot (or Thoth): He is the creator god according to the cosmogony of Hermopolis, and is considered the deity of wisdom and writing, thus being the patron of scribes and protector of sciences and arts. In addition to being worshipped in Hermopolis, he was also venerated in other widely dispersed places, such as Sarabit al-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula. He was a lunar god, timekeeper, and creator of days according to Egyptian religion. He was usually represented with a human body and the head of an ibis (a bird with a long neck and curved beak).

- Uadyet (or Wadjet): She is a goddess related to the strength of certain natural phenomena, such as the scorching heat of the sun and the growth of plants. Her main iconographic element was the cobra, known as the ureus, although she also appeared as a lioness with a solar disk. She was the daughter of Anubis and protector of Lower Egypt, being worshipped in places such as Tanis and Buto. She also protected the pharaohs and, in fact, the ureus was one of the most commonly used symbols by them, present in the Red Crown of Lower Egypt and in funerary masks.

In addition to all the enumerated gods, in Egyptian religion there were other supernatural characters that were important for giving meaning to the myths. For example, Ammut, who was responsible for devouring the hearts of the deceased who had not been pure in their lives, was represented in a body that combined the lion, crocodile, and hippopotamus.

Special mention should also be made of the sphinxes, mythological beings indissolubly linked to Egyptian religion (although there are also other versions in ancient cultures). In this case, they were creatures formed by a lion’s body with a human head, often identified with that of the pharaoh. But within the sphinx archetype, there are variations, as from the Middle Kingdom, the mane and ears were also lion-like, leaving only the pharaoh’s face. In any case, their magical function was the protection of temples or sacred places, with the most famous being the Great Sphinx of Giza, next to the famous Pyramids, which could represent the pharaoh Kefren.

Other important symbols in Egyptian religion

As we have seen, there are several symbols that are prevalent in Egyptian religion and are worth examining. You will often come across these symbols in temples or in the Books of the Dead exhibited in museums, which we will explain below.

- Eyes: These entities represent an extension of a specific god, possessing magical powers for healing or protection. They could appear accompanied by symbols associated with that god or with royal power. The two most famous eyes were the Eye of Ra and the Eye of Horus, the latter often used in the form of amulets.

- Ankh: This hieroglyph, also known as the Egyptian cross, takes its name from its shape. It means “life” and is sometimes referred to as the “key of life.” When held by a god, it usually indicates that the god has power over life or death. If accompanying a human, it typically indicates a search for immortality. Initially, only pharaohs could aspire to this quest, but in the New Kingdom, it extended to all mortals, as evidenced by the Books of the Dead. Interestingly, the early Copts used it as their own symbol due to its obvious resemblance to the Christian cross.

- Uraeus: This is the representation of an erect cobra and is an invocation to the goddess Wadjet, the protector of the pharaohs according to Egyptian religion. Therefore, it is common to see it on the funerary masks of pharaohs, such as the famous one of Tutankhamun. At times, the uraeus also bore the crowns of Upper Egypt (red) and Lower Egypt (white).

- Uas scepter: This is a staff of authority that symbolizes strength and power, designed with the head of a fabulous animal at its upper end. As a result, it was often carried by significant gods such as Ptah and Osiris. It also appears associated with some pharaohs, such as Ramses II and Tutankhamun. In fact, the city of Thebes (named by the Greeks for unknown reasons) was called by the Egyptians Waset, which would mean “city of the scepters,” as this was the capital starting from the Middle Kingdom. Its origin is uncertain, although it could have come from the staffs that shepherds used to guide their livestock.

- Cayado (or heqa): Similar in meaning and origin to the uas scepter, this symbol can be shorter and has a curved handle at the top, without a fantastic animal.

- Dyed pillar: This symbol represents stability and was used since the Archaic Period, remaining in use until the end of Egyptian civilization. It consists of a column with bound sheaves of reeds or branches, possibly representing a tree trunk or the spine of the god Osiris, a major figure in Egyptian religion.

- Menat: A chest ornament made of hard or soft materials like glazed ceramic or leather. It is composed of numerous beads attached to a counterweight on the back, sometimes held in the hand as an amulet. This symbol is closely linked to the goddess Hathor, and her priestesses could use it as a rattle.

- Nejej: Known in agriculture as a flail, this tool consists of two rods joined by straps and was used for threshing grains, thus symbolizing agricultural prosperity.

- Crowns: Not all Egyptian crowns had a strictly religious meaning, but they are often depicted in relation to pharaohs and gods. The main types are:

- White crown or Hedyet: Symbol of Upper Egypt, it is white, has a conical trunk shape, and a rounded top.

- Atef crown: A more elaborate version of the Hedyet crown, with ostrich feathers on both sides. It is often worn by the goddess Nejbet, who was highly venerated in Upper Egypt.

- Red crown or Desheret: Symbol of Lower Egypt, it is red, has a narrower top than the Hedyet crown, and a curled finish, perhaps representing the bee, an important symbol of this region. It was worn by various deities, especially Uadyet, protector of Lower Egypt.

- Double crown or Sejemty: The combination of the Hedyet and Desheret crowns, symbolizing the union of Upper and Lower Egypt, so it was often worn by pharaohs.

- Shuty crown: Another crown symbolizing the union of both regions and their corresponding protective deities (Uadyet and Nejbet). It consists of two large symmetrical hawk feathers, sometimes with horns and a sun disk added.

The Temple and Priests in Ancient Egyptian religion

The temple was a common element in all of Egyptian religion. It was the center of society, and the heart of every settlement, from large cities to small villages. The temple served not only religious purposes but also administrative, medical, and educational functions. Other sacred places in later religions, such as Christian cathedrals or Muslim mosques, also had similar social roles.

However, there was a significant difference between Egyptian temples and those of other religions, such as those mentioned. In Egyptian temples, the faithful did not gather inside; instead, it was a space only accessible to pharaohs or priests, who acted as intermediaries between the gods and the people. The faithful could only enter the hypostyle halls or open peristyles. For a more technical and artistic explanation of Egyptian temple architecture, please visit the page dedicated to architecture in Ancient Egypt.

Therefore, the clergy held a crucial position in Egyptian civilization. Among other things, their duty was to honor the deity who served as the patron of the temple daily, with offerings to the deity’s image, located in the inner sanctuary. Typically, this was a statue that, according to Egyptian religious belief, housed the ba or soul of the god.

These priests were part of a highly hierarchical body, with assistants to complete all tasks, and there was a place for women as well. In addition, positions were hereditary, passed down from fathers to sons, maintaining great secrecy in their practices and knowledge. Some of these priests specialized in different functions, such as those responsible for funeral rites or observing the stars for making certain decisions.

Related to this are the oracles, which had a significant presence in Egyptian religion, especially from the New Kingdom onwards. It was also the priests who were responsible for asking the deity about all kinds of issues, from matters of government to more mundane doubts. They interpreted signals such as the movements of a boat as answers. These intercessions were usually performed in the temple, but there were also sacred enclosures dedicated specifically to this task. The most famous of these was the Oracle of Amun at Siwa, which was even consulted by Alexander the Great.

Some of these consultations were carried out in large rituals and official festivities, although these events could have many other objectives, such as the celebration of the ascension to the throne of a new pharaoh. Some of these festivities were really massive, such as the Opet festival, which took place in the temple of Karnak, where the gods Amun-Ra, Mut and Khonsu (the Theban triad) were carried in procession on a boat. On the other hand, the daily and morning rituals were carried out in a much more intimate manner and only by priests and assistants.

Life After Death

The religion of ancient Egypt went beyond explaining the “before” and “during” phases of existence and also addressed the “after” phase of earthly life. Death was seen as a natural part of the cyclical nature of existence, marking the transition from the earthly realm to the afterlife. According to this belief, at death the physical body separated from the immaterial components of the individual’s personality, namely the ba or soul and the ka or vital energy.

Although these components dispersed throughout the universe, they could regenerate indefinitely, as long as a crucial requirement was met: the corporeal remains of the deceased (i.e. the body) had to remain intact.

Hence, the practice of mummification, which is one of the distinctive features of ancient Egyptian religion. Some scholars refer to it as a “magic curtain” that enables access to eternal life and that extends to the sarcophagus itself. However, the ritual also involved other elements, such as the careful preparation of the body through desiccation, removal of organs, and embalming, among other procedures.

Funerary objects were also deposited in the tombs of the deceased. Some were believed to be needed by the individual in the afterlife, while others served as protective amulets. The wealth and status of the individual were reflected in the richness of their funerary belongings.

The Book of the Dead and the Judgment of Osiris

One of the most fascinating religious, literary, and artistic expressions of Ancient Egypt is the Book of the Dead. This papyrus text, richly decorated with images, aimed to help the deceased achieve eternal life, which was enjoyed in the fields of Aaru (the Egyptian version of paradise).

Its origin can be traced back to the texts written on the walls of pyramids and sarcophagi, as early as the Old Kingdom in the third millennium BCE. It consists of spells that guide, warn, and protect the deceased from dark forces, present them to the gods, and perform many other tasks. For a more detailed explanation of its structure and style, you can visit the page devoted to Egyptian writing.

The Book of the Dead is closely related, therefore, to the Judgment of Osiris, one of the most important myths in Egyptian religion. It determined who achieved eternal life and who had to face their “second” and final death (being devoured by Ammit).

This was done by direct weighing on a balance. On one tray was placed a feather of Maat (the goddess of truth and justice), and on the other was the heart of the deceased, which had been extracted by the god Anubis. At that moment, a jury of gods asked the deceased questions about their earthly behavior, and based on their answers, the heart would enlarge or shrink, increasing or decreasing in weight. Only if, at the end of the interrogation, the heart was lighter than the feather of Maat, could the deceased’s immaterial components (ka and ba) unite with the mummy and access the fields of Aaru.