If you love traveling and visiting museums, then you know that understanding the keys to appreciating art is essential to fully savor its value. The art of Ancient Egypt is no exception. To truly admire its exceptional artistic pieces, it’s important to know their secrets – what they represent, why they were created in that style, and their historical context.

That’s where we come in. Our page is dedicated to exploring the art of Ancient Egypt, with a focus on its main visual arts including painting, relief, sculpture, and ceramics. We have a separate page dedicated to the importance of architecture in this civilization. As artists often say, “educate your eye” before embarking on your journey. You can rely on our agency to discover the best artistic pieces of this unparalleled civilization. Get ready to be fascinated!

One of the most important things to keep in mind about Ancient Egyptian art is that it was primarily created for religious purposes. Virtually all artistic production in this civilization aimed to please and invoke the gods while also helping the deceased achieve eternal life in the afterlife. You can find more details about this on our page dedicated to Egyptian religion.

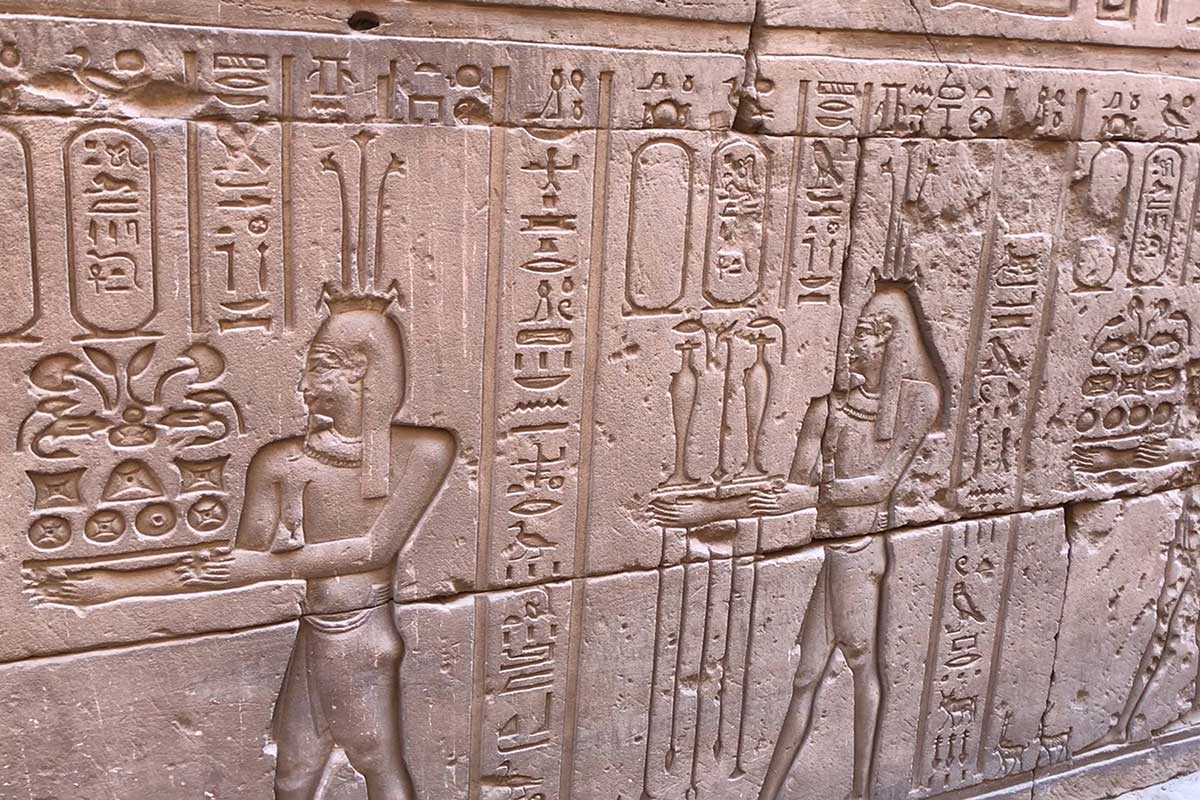

As a result, the most common themes in Egyptian art are representations of the gods and pharaohs, as well as supernatural creatures that were part of the religious imagination, such as sphinxes and animals that often symbolized those divinities. Environmental elements, such as plants and geographic features, were used to give shape and meaning to mythological scenes, rather than to represent a landscape itself. Most of these artworks were located in sacred places, such as temples and funerary enclosures.

Another important characteristic of Egyptian art is the use of specific canons that remained largely unchanged throughout the more than three millennia of that ancient civilization. As we explore in the sections dedicated to painting, relief, and sculpture, these canons were conventions used to depict the human figure and the supernatural attributes associated with it, as most of the painted or carved figures referred to deified gods or pharaohs.

The wide variety of materials used in Egyptian art is also noteworthy. In many cases, these materials had high value and were used for projects promoted by the pharaohs, directly linked to the most sought-after goal in this civilization: to achieve eternal life in the afterlife. Examples include ivory for small pieces of funerary equipment, quartzite for sculptures, and malachite and lapis lazuli for pigments in paintings. And, of course, gold, the preferred metal of the pharaohs for artistic works such as funerary masks and jewelry.

Unfortunately, many of the masterpieces of Egyptian art are located in other countries, in museums such as the British Museum in London, the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, or the Louvre in Paris. However, mentioning them helps us better understand the characteristics and meaning of Egyptian art, as there are still pieces of incalculable value preserved here, either in museums or in their original location for which they were conceived.

While the primary purpose of Ancient Egyptian art was religious and funerary, it was expressed in a variety of forms. The artists of this civilization were skilled in various plastic disciplines, which are discussed below: painting, sculpture (bas-relief, high relief, or round sculpture), and ceramics as the most everyday form of expression.

Painting was one of the most prominent art forms in Ancient Egypt and reached a high level of technical mastery, considering that these works were created several millennia ago. This is especially evident in mural painting, which can be considered a forerunner to fresco painting that was used many centuries later.

The exceptional technical prowess is exemplified by the preparation of pigments. The mixtures used produced extremely high-quality results, particularly in terms of durability, which was further aided by the stable conditions (temperature and humidity) of their location, which were often underground or within rock. This has allowed the paintings to remain well-preserved for thousands of years.

Ancient Egyptian painters had a sophisticated method of obtaining pigments, using natural materials found locally such as soils of different shades, which they mixed with clay and dissolved in water. These mixtures were then agglomerated with egg and glue, among other options, making them pioneers in the tempera technique. Fresco painting was also used, particularly for mural paintings, where the pigments were transferred to the layer of plaster. Papyrus was another common support for this art discipline, particularly for the Books of the Dead.

There were six main colors used in Ancient Egyptian painting, all of which were obtained from local sources:

Despite the limited color palette, Ancient Egyptian art compensated for this limitation with the symbolic and visual power of the colors. Moreover, the technical virtuosity of Ancient Egyptian painters was reflected in the preparation of pigments, which offered extremely high-quality and durable results.

A good example of this is the different skin tones that the divinities could adopt, which referred to their powers. For instance, the color green was typically associated with agricultural fertility, as in the case of Osiris, while blue alluded to the cosmic or celestial character of their corresponding deity, as in the case of Amun. White was often used to symbolize purity, such as when representing mummies.

Black, on the other hand, conveyed the idea of night and death, but it was not necessarily negative, as it was seen as a prelude to resurrection. Red was used to represent blood and life and was used for the skin of male human figures. Yellow, a symbol of the sun and eternity, was typically used on female human bodies.

Another characteristic of Ancient Egyptian art, particularly in painting, is its unique canon for representing the human figure, which is commonly known as the “profile canon.” This canon is called as such because artists combined some parts of the body from the side and others from the front. Specifically, it usually followed this scheme:

While some might think that the profile canon was a sign of the artist’s incapacity, the truth is that it has a symbolic-religious character, which was applied mainly to earthly beings with aspirations of eternity in the afterlife, such as pharaohs and the deceased in general. According to their religious beliefs, the drawing of a deceased person directly invoked them in the afterlife, as if in direct communication with them. Therefore, it was important that the deceased always showed the most important part of their ba or soul, which was their inner gaze housed in the eye and their heart housed in the torso.

In Ancient Egyptian art, the figures and elements of the scene lack volume and are two-dimensional, always flat and without faithfully representing spatial depth. However, to express the idea of distance or depth, artists used the superposition of profiles. This meant that the farthest figures stood out in height and were partially covered by the closest figure.

In terms of the proportions of the figures, a hierarchical order expressed in size was often observed. For example, the pharaoh was usually depicted in larger dimensions than the rest of the human characters unless the aforementioned spatial rule of profile superposition was applied.

The profile canon and spatial conventions remained in force in Egyptian art for more than three millennia, from its earliest phases. Only in the 1st century AD, under Roman domination, were these canons ignored to a certain extent, as Roman artistic canons were imported.

This break from canons under Roman rule led to the emergence of a transcendent genre, not only for the history of Egyptian art but for the history of universal art: the portrait. The fascinating portraits of El Fayum, found in the necropolis of Hawara near the oasis of El Fayum, are now housed in the Louvre Museum in Paris. These portraits were painted on the corresponding part of the sarcophagus head with surprising naturalism, worthy of the best works of the Italian Renaissance. This was a clear intention to show the mummy housed inside with realism.

Sculpture is one of the most significant disciplines in Ancient Egyptian art and is closely linked to architecture, taking the form of either high relief, where the motifs protrude greatly from the background surface, almost becoming a freestanding sculpture, or bas-relief, where the motifs slightly protrude from the background surface.

The bas-relief can be considered a form of expression that is halfway between painting and sculpture. It is mainly made from rocks of various types such as sandstone, limestone, shale, and other materials. It undoubtedly has more affinity with painting, from which it takes its primary characteristics: the profile canon, the hierarchical order of the figures according to their size, and the absence of depth.

These characteristics can be seen in the Narmer Palette, a valuable slate plaque not only for Egyptian art but also for its political history. It is considered by many as the foundational milestone of the Old Kingdom, where the same king (Narmer) wears the crowns of Lower Egypt and Upper Egypt. The palette is on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Furthermore, these bas-reliefs were frequently painted in various colors, resembling mural paintings. They were commonly placed on the walls of constructions, especially in temples, sometimes serving as their main attraction. The pylons provided an impressive entrance for the faithful with their magnificent, large and colorful bas-reliefs. The technique was also used on obelisks, which were completely adorned with bas-reliefs. In interior spaces, iconographic programs were frequently carved into the columns of hypostyle halls or rooms. The sanctuary was also extensively decorated with engravings and mural paintings, making it one of the most adorned areas.

In these spaces, hieroglyphics held significant importance, as in all disciplines of Egyptian art. They were often carved or engraved on the surface, frequently filling the entire space between figures, resulting in horror vacui that would leave visitors in awe. For more information on hieroglyphics, please visit the Writing in Egypt page.

Lastly, cosmetic palettes can be considered genuine sculptural works, crafted from high-quality wood and other lightweight materials. These items were used to hold beauty and body care products and were decorated with human figures of great artistic value, following the bas-relief canons.

Sculpture in the round and large high reliefs present a different aspect in Ancient Egyptian art. In these works, the representation of the figure is three-dimensional in itself, unlike the two dimensions of painting and low relief. However, despite allowing a wider view, such as the 360º view in round sculptures, the law of frontality always prevailed. That is, the works were conceived to be viewed from the front, so the profile canon loses its meaning here.

Another unmistakable feature of sculpture and, in general, all art in Egypt is the hieratic style. This term refers to the solemn, rigid, and expressionless gesture of the characters, which is done as a sign of respect and divinization, in the case of the pharaohs. One of the most spectacular and famous examples is the sculptural group of King Mycerinus, flanked by the gods Hathor and Hardai, located in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Other iconographic characteristics and canons that repeat throughout the different periods of Egyptian art can also be observed. For example, a greater fidelity to nature when representing the human figure, although idealized in the case of the pharaohs. For other protagonists, such as courtiers, realism is more pronounced, with little dissimulation or idealization.

These types of works show, better than any other object of Egyptian art, the iconographic canons for representing pharaohs. The statues, funerary masks, and sarcophagi captivate us, for example, with the classic nemes: a cloth headdress tied at the back, which in many cases was made of gold and lapis lazuli. They also allow us to better appreciate the ureus: an upright cobra at forehead height representing the protection of the goddess Wadjet, or the prominent beard (false, by the way) to identify with the god Osiris. The usekh collar is also noteworthy, used as a talisman and invocation of the goddess Hathor.

The art of ancient Egypt displayed a remarkable mastery of technique, as evidenced by the aforementioned idealized naturalism. Artists worked with stones of varying hardness and quality, achieving polished finishes of great perfection. Among the materials used were diorite, granite, and basalt, as well as ivory, gold, and bronze (sometimes gilded). This demonstrated the sophisticated knowledge of metallurgy by Egyptian sculptors and goldsmiths. Silver was also used in some pieces, likely acquired through effective trading networks.

Full-body figures were a common typology in ancient Egyptian art, particularly in depictions of pharaohs standing or sitting on thrones. Scribes, on the other hand, were often portrayed sitting on the ground with flexed legs. Busts were also prominent, with the famous example of Nefertiti showcasing the idealization of women through stylization of the neck. This feature, however, can be attributed to specific stylistic conventions of the Amarna Period (New Kingdom), which was a revolutionary period in religion and art in Egypt.

Colossal-sized sculptures were also a significant feature of ancient Egyptian art, found in many monuments throughout the country. These sculptures included sphinxes of gigantic dimensions associated with temples or funerary enclosures, as well as representations of divinized pharaohs like Ramses II in Abu Simbel.

Small figurines were frequently included in tombs, depicting not only the deceased but also divinities and mythological characters that could provide support and strength in the afterlife. Materials like ivory, minerals with special characteristics, and precious metals were commonly used for these figurines, as well as for necklaces and jewelry that were often worn as amulets.

Ceramics were an important medium for artistic expression in ancient Egypt, with interesting productions dating back to the predynastic period (Naqada periods).

Pottery making was a common occupation in Egyptian society, with ceramic objects serving a range of functions from everyday use to funerary and religious practices. Everyday objects such as cooking, preserving food, or containing perfums, among many others, were often decorated with simple geometric shapes or schematic figures.

But the most valuable works were precisely those intended for funerary purposes, as they were placed next to the tombs to provide different services to the deceased in the afterlife. In this sense, glazed pieces with varnish and parts covered with gold in some cases were produced. Alabaster or ivory were also materials used as complements, in this and other disciplines of Egyptian art.

The canopic jars, in particular, were notable works of funerary ceramics. These containers were used to hold the viscera of the deceased, which had to be washed, embalmed, and preserved to ensure the deceased’s eternal life in the afterlife, where they would be reunited with their preserved body (mummy) and immaterial entities (ba and ka). Initially, they were simply decorated with hieroglyphic inscriptions and closed with a slab, but in the New Kingdom, the lids took on the form of the head of the deceased and, later, that of the protective divinity.

Funerary ceramics also produced other masterpieces of Ancient Egyptian art, including the ushabti. These figurines, meaning “those who respond to calls,” were placed next to the tomb of the deceased to work for them in the afterlife. Faience, a type of glazed ceramic known for its fineness and eye-catching finishes in colors such as ochre and blue in different shades, was commonly used to create ushabti. However, they could also be made from other materials such as wood or lapis lazuli. The beauty and skill of Egyptian ceramic art demonstrated the mastery of the Egyptians in working with different materials and techniques to create both functional and artistic objects.

Fill out the form below to receive a free, no-obligation, tailor-made quote from an agency specialized in Egypt.

Travel agency and DMC specializing in private and tailor-made trips to Egypt.

Mandala Tours, S.L, NIF: B51037471

License: C.I.AN-187782-3

Customer reviews showcase the level and quality of service a website provides.

Trustindex collaborates with 133 review platforms to provide website visitors easy access to all real and verified reviews in one place.

Reviews from other platforms are displayed and added to the ratings only if they are proven spam-free and meet Trustindex's guidelines.

Trustindex continuously measures the satisfaction of your customers based on evaluations. Less than 1% of the customers surveyed indicated a problem.

The website's contact information and business information has been independently verified by Trustindex.

The website is constantly checked for security issues by Trustindex.

Websites that continuously maintain a high level of customer satisfaction and comply with a high level of security protocol can obtain a Trustindex certificate. When shopping, look for Trustindex certificates and buy with confidence.

More details »

For businesses

Build trust and increase sales with Trustindex certification.

More details »